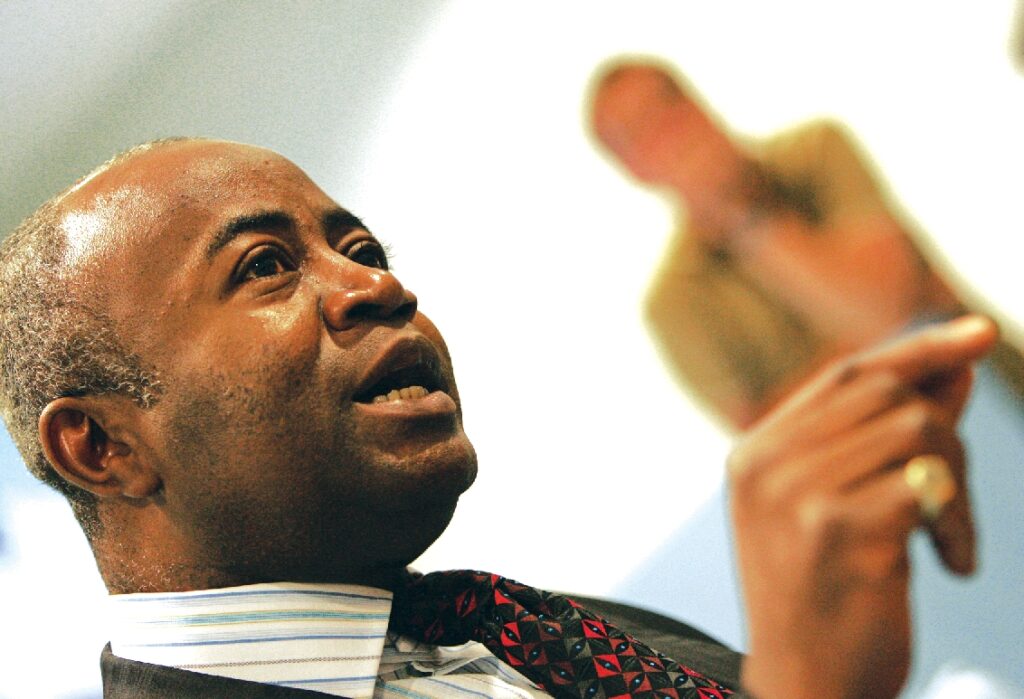

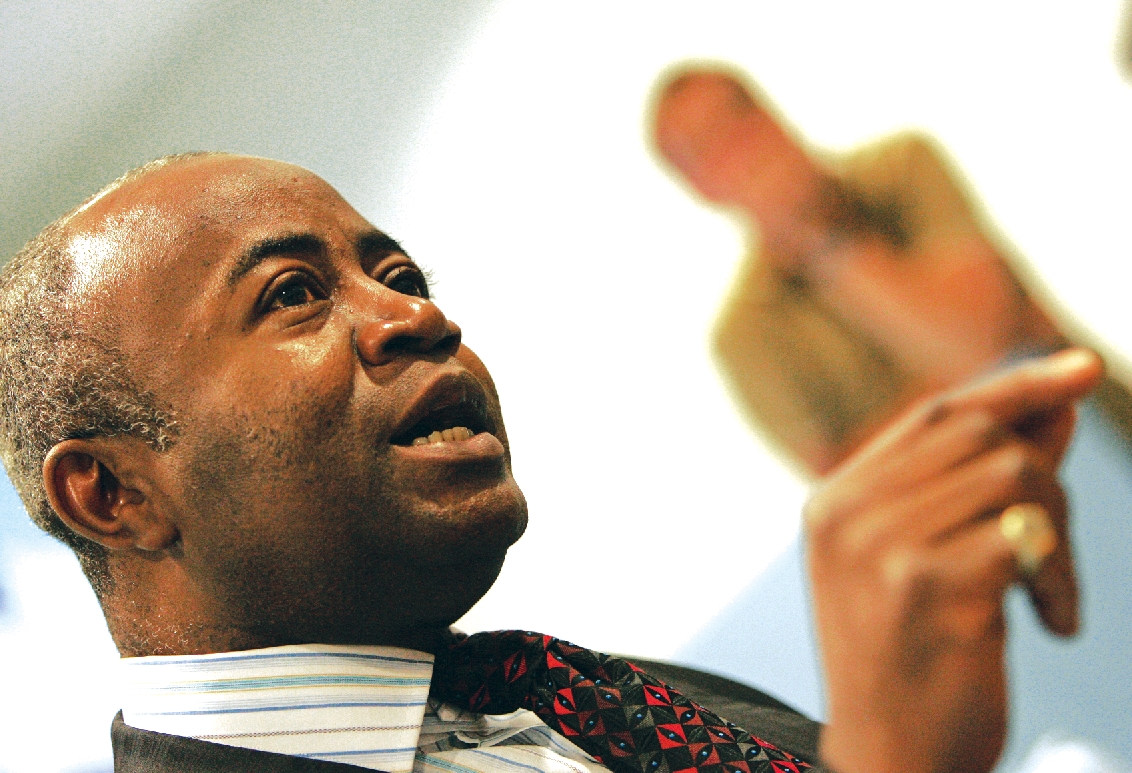

The news arrived subtly, a ripple from across the Atlantic, yet it stirred deep currents in the Liberian consciousness. Courtenay Griffiths, the formidable British barrister who served as the lead defense counsel for former Liberian President Charles Taylor during his landmark war crimes trial, died this week at the age of 70. The announcement by The Residual Special Court for Sierra Leone, delivered on Tuesday, May 24, 2025, sparked a moment of grim reflection across the West African nation: what remains of the “Liberian Warlord,” years after his conviction and imprisonment, and why does his shadow still loom so large over a political landscape ostensibly free of his direct grasp?

Charles Ghankay Taylor, once the charismatic, enigmatic figure who ignited Liberia’s brutal civil war and became a central player in regional destabilization, now resides within the stark confines of HMP Frankland in the United Kingdom. Convicted in 2012 by the Special Court for Sierra Leone on 11 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity – including acts of terrorism, murder, rape, sexual slavery, and the use of child soldiers – he was sentenced to 50 years. The verdict cemented his place in history as the first former head of state to be convicted by an international court since Nuremberg. Yet, for many Liberians, his physical absence has not entirely erased his pervasive influence.

Taylor’s story is inextricably woven into the fabric of Liberia’s modern tragedy. On Christmas Eve 1989, he launched an incursion from Ivory Coast, leading the National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL) against the increasingly authoritarian regime of Samuel K. Doe, a master sergeant who had himself seized power in a bloody 1980 coup. Taylor, a former Doe official, promised liberation, but his rebellion spiraled into a devastating conflict marked by extreme brutality, child soldiers, and widespread atrocities. As various factions emerged and the state collapsed, Taylor’s NPFL gained control of vast swathes of the country, fueled by resource extraction, particularly timber and diamonds.

The conflict, however, refused to be contained within Liberia’s borders. Taylor’s ambitions and strategic alliances famously spilled over into neighboring Sierra Leone, where he provided crucial support, including arms and training, to the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), led by Foday Sankoh. In exchange for this backing, Taylor allegedly received “blood diamonds,” which funded his own war machine and regional machinations. The RUF became notorious for its extreme violence, systematic mutilations, and the widespread use of child combatants, leaving Sierra Leone equally ravaged by a decade-long civil war that closely mirrored Liberia’s horror.

Within Liberia, Taylor’s rule, even after he won the 1997 presidential election on a platform of “he killed my ma, he killed my pa, but I will vote for him,” continued to be characterized by “gambling politics bent on supremacy.” The nation’s political system, often dominated by a powerful elite, has historically been a high-stakes game where personal ambition and control of resources frequently trump national interest. Taylor, a master of political maneuvering and intimidation, epitomized this high-stakes environment. Even in his absence, the fear persists among some political elites and segments of the population that a future, perhaps distant, release or even continued influence from afar, could destabilize the fragile peace and disrupt their carefully constructed power structures. The specter of a “Taylor return” – whether literal or symbolic – is often invoked in political discourse, a potent reminder of the unresolved issues of justice, impunity, and the enduring quest for true accountability.

Courtenay Griffiths, the tenacious advocate who fought tirelessly for Taylor’s acquittal, often highlighted the political nature of his client’s prosecution. His death now closes a significant chapter in the legal saga, but it does little to silence the quiet anxieties that still plague Liberia. The nation, currently undertaking its own complex process of reconciliation, as seen in the recent reburial of Samuel Doe, grapples with a past that simply refuses to fade. Taylor’s confinement serves as a form of justice for the thousands of victims, yet the lingering fear of his historical echo, woven into the very fabric of Liberian politics and its ambitious, sometimes ruthless, elite, underscores just how profoundly his actions continue to shape the destiny of a nation striving, against immense odds, for an elusive and lasting peace.

By: TPA News Desk | editor@thepointafricanews.com | Editor’s Pick

Leave a Reply